How do Mobile Apps Make Money?

So you’re sitting at home, browsing the internet as per usual (too much Reddit, I know…we’re all guilty of the same pleasure) and you open up another tab to see some news updates. Troubles in another country, a fire put out by firefighters (maybe even a kitty or two saved), and other news like these. The usual stuff.

Suddenly you reach an article about a new wonder app, maybe a new social media app that’s all the rave. Heck, even some of your friends are hopping in on the digital train. After perusing the article and even trying the app for yourself, you wonder:

Ok, this is fun and all. But how is it free? Why is it free? Is it really free?

Then you spiral down the rabbit hole, ultimately asking yourself:

Ok, but how do they make money? How do apps make money?

Well, there are a number of different avenues to be touched here. There is a multitude of ways to make money from an app, and we will try to cover the main ones in this article.

Ads

You know those pesky little ads, right? They pop-up when you least expect them and get obnoxiously difficult to turn off at times. As annoying they may seem to you, as loved they are by app creators.

In-app advertising has been providing a stable revenue stream for app creators since 2010 when Google out-bid Apple in a deal for AdMob. Since then, a number of other advertising platforms have replicated AdMob’s model, such as AdColony, TubeMogul and Airpush.

Now, the elephant in the room. How much money can you make with ads?

Well, it depends. “On what?” you might ask. On a lot of things, such as user interaction (how many of them tap on the ads, watch the ads, etc.), the relevancy of the ads, number of downloads, etc.

But if you could narrow it down to one single factor, that would be the number of active users the app has. While it’s important to have a large number of users downloading the app, it’s equally important to have an active user base that uses your app on a daily basis, so that they also interact with your ads.

For example, App creator Rich Woods created a slot machine game that incorporated ads, named Cherry Chaser Slot Machine. After getting 300k downloads with no upfront investment, he started earning $100 a day after one month since launching the app. Needless to say, it’s a working model that prompted him to release more slot machine games on Google’s Play Store.

Another example. Balloon Island created several popular games that garnered downloads in the millions. Thanks to the ads, the company was raking in sums of over $2,000 per day. Astonishing.

Of course, you might say that all that sounds great, but there must be some setbacks, such as:

- People hate ads. Even I get annoyed by them. Why would I put ads in my app?

- How can I control what ads get shown to my userbase and which are not?

- Surely ads get a cut, why would I pick them?

Let’s start with the most obvious one.

People hate ads

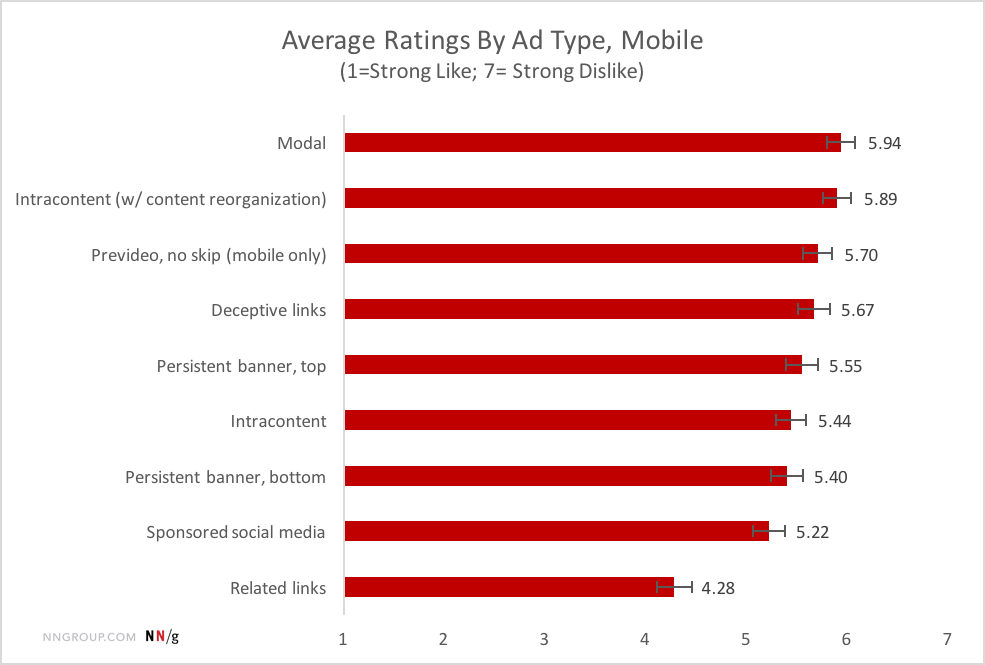

This 2017 survey of over 452 adult respondents from the United States who were not employed in the IT or Marketing industries (so no job-related bias there) brings to light interesting insights with regards to the types of mobile ads that most people find annoying.

As you can see, modal ads (the ones that pop-up when you use an app) were the most disliked of the bunch, even more than deceptive links, which purportedly redirect the user to something he doesn’t expect to see.

Statistically, users were more annoyed by having ads pop-up at random when using an app than accessing deceptive links. It’s to be expected, as modal ads represent obvious friction between the user and his experience. That is, two types of friction.

The obvious one, action friction, which forces the user to take an extra step to get back to what he was doing (i.e. close the ad) and cognitive friction, which provides unexpected behaviors in a previously established frame of mind (i.e. Up until now what I saw was what I got, until it wasn’t).

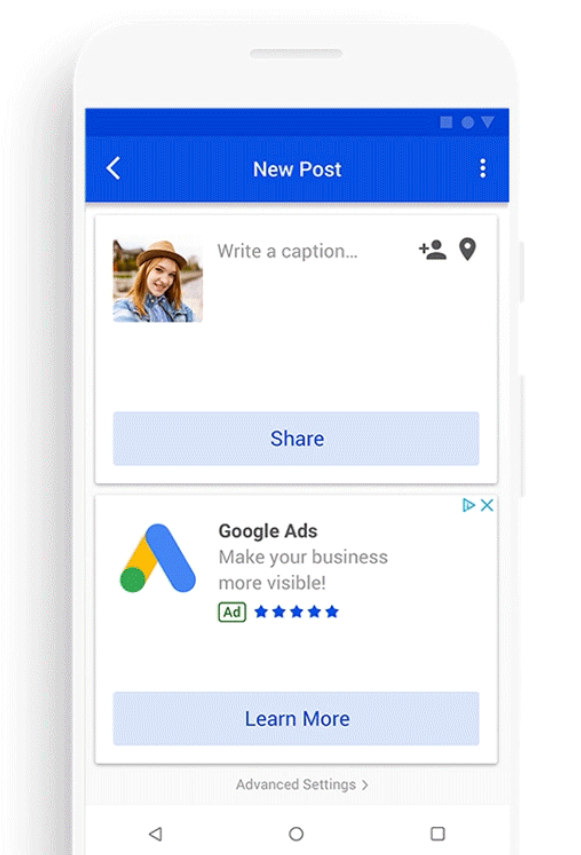

Intracontent ad that uses the same layout and styleguide of the app to blend in naturally

The intracontent (meaning ads that blend in with regular content) and persistent banners are ranked lower in the list of annoyances. This is because intracontent ads emulate the layout of the app content, which provides less of a disruption (less cognitive friction) than let’s say, modal ads.

As for banner ads, they generally don’t interfere with the regular flow of an app (sitting in a non-intrusive part of the app).

Even though people might get a bit turned off by the ads, it’s important to note the three surface-level reasons why this happens:

- General distaste of ads

- Inaccurate ads that do not target any underlying needs of the user

- Obtrusive ads

While the first one is something that comes on a case-by-case basis and is uncontrollable, the last two definitely fit under the product owner’s (i.e. you) hands.

You have a certain degree of control, as you can set which categories of ads that benefits your user base and also not go for obtrusive ad types, such as interstitial (fullscreen videos) or deceptive links.

Plus, you can always blend together multiple business models. This means having, for example, both ads and in-app purchases, which leaves it to the user to permanently turn off ads by placing a purchase.

How can I control what ads are shown to my users?

Generally, mobile ad platforms provide you with a dashboard that lets you approve or reject which ads can be shown within your app. For example, Admob provides both coarser (per category) and finer controls (per specific ad).

Being able to control which ads are shown in your app is important, as you wouldn’t want to have, for example, political ads in a productivity app. So this issue is generally covered.

But how much do they cost?

Nothing. Advertisers want eyeballs, and eyeballs are hard to reach. Attention is a zero-sum game, meaning that it cannot scale between individuals.

One person can pay attention to one thing at a time (multitasking is a matter of perception, not something objective).

Because advertisers want a better reach to users’ eyeballs, they pay ad providers such as Google a small fee each time a user taps on an ad.

Thus, one of Google’s objective is to have as many apps use its ad platform. That’s why ads work best with large user bases (hence advertisers relishing social media apps).

And, in order to achieve this goal, they make it as easy as possible to integrate it (the financial aspect being that it’s free). Since the bulk of Google’s revenue is coming from ads (72% of its revenue for Q1 of 2020 came from ads) you bet they try to make it as friendly as possible to integrate, distribute and use their ad platforms.

So what do ads cost? Nothing except the implementation costs, which can fluctuate depending on what type of ads you want to integrate.

If you want intracontent ads, they might require extra design work (though, generally, you would reuse the existing design). So basically, not a lot.

As an aside, if an ad provider ever wants to charge you money for integrating their services in your app, then two things might happen: either the world starts to rotate in the opposite direction, or the job of an advertiser will be the most sought out one on the market. So basically the first option.

Subscriptions

As we’re slowly entering the “Everything-as-a-service” Age, subscriptions are becoming a safe-haven for companies. When software was first starting to be sold commercially, pay-to-use subscriptions were quite rare. Usually, you used to buy the software with a one-time fee, and either receive updates for free or pay for them as needed.

Given the dot-com crash of the 2000s (of which we spoke in our book) and a range of other causes, tech companies started to see the need for a more consistent revenue stream.

As such, more and more businesses started to adopt the subscription model, much to their success (such as our own Appointfix and FieldVibe). Treating software as a service has been normalized for a while now, for the benefit of everybody.

A more consistent revenue stream means there is more capital to invest in the product, which in turn makes it a better product, which becomes used by more people.

As for how much money do apps make with subscriptions, it’s a pretty easy equation: (Plan fee x plan users) then adding the numbers together. Let’s do some quick napkin math.

Let’s say an app has three plans:

- Basic – $4.99 with 300k users

- Premium – $7.99 with 700k users

- Ultimate – $9.99 with 500k users

For the sake of simplicity, we’ll calculate on a recurring month-by-month basis (given the fact that some companies also leave the option of yearly payments).

Basic users rake in $1,497,000.00 in revenue / month, premium users $5,593,000.00 / / month and finally Ultimate users $4,995,000.00 / month.

With a total of $12,085,000.00 / month.

Of course, this is a simplified version just to make you understand the process. From this $12,085,000.00 some costs are automatically withdrawn, such as Apple taking a 30% commission off of every sale through its App store (not to mention all the costs of maintaining a top-tier application in today’s competitive market).

Subscriptions can also be paired with in-app purchases. For example, for FieldVibe we give the opportunity to clients to buy as many SMS reminders as they need, regardless of the plan they’re on. So, if they’re happily satisfied with the plan they’re on but want extra SMS reminders, they can get them separately.

Paid

Even though the SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) industry is booming and companies are seeing the benefits of consistent revenue flow, some applications hold on to the classical one-time fee.

Currently, the apps that go for a one-time fee are generally games. This can also work for other types of apps (such as productivity), but it’s rather unusual.

Paid apps can also be coupled with in-app purchases. Even though users can buy the full app, to get ahead (and not grind for hours), they can pay for specific in-app products that can advance them in their adventure.

There’s not much to say about the tried and true one-time fee paid app model. It’s certainly not for everybody, and you can make a rough guesstimate on how much money an app makes (before paying for all it’s underlying expenses), by multiplying the number of users with the price of the app.

In-app purchases

The subject of many controversies, in-app purchases (also known as microtransactions) are products that exist within the application. They can come under the form of in-app assets, such as extra lives (for video-games), extra SMS reminders, ad removals, etc.

Generally, they fit under the app’s marketplace, where the user can see them and buy them. The advantage of having in-app purchases is that there isn’t a one-to-one relationship between them and the user, like with subscriptions.

Thus, a single user can buy many transactions (practically, unlimited) as opposed to a single subscription at a time. This high-volume-low-price strategy is favored by mobile game developers. The nature of a videogame is that many of the items that influence gameplay can be monetized, translating directly into in-app products.

If for the previous models it was (roughly) easy to calculate the gross revenue margin, for apps that incorporate in-app purchases it’s even harder.

Depending on what your app does, it’s important to balance out the in-app purchases so that they solve the user’s needs. Also, keep in mind that coming up with the best in-app purchases is a balancing act, especially with videogames.

For example, if by buying in-app products users can become near-invincible by creating an “unnatural” imbalance, then people who don’t invest money in the game will get immensely frustrated and forfeit or even bring a bad name to your game.

Overall, in-app purchases can be great tools (and revenue streams) for your product if they are well thought out. Better yet, they work best together with other revenue models such as ads.

Partnerships

Partnerships connect different communities together.

As a product owner, you might be approached by other businesses in order to promote their services. These regularly come at a later date, after the user base of your app is established and has grown to a significant size.

But, the opposite approach can be taken as well. When analyzing the feasibility of your product (the Business Analysis chapter in our book) you might also want to consider the possibility of building your features in such a way as to encourage sponsorships (such as having a feature to create custom discounts for different brands in your app).

Ultimately, it’s still about the concentration of eyeballs. A large audience means a high possibility of a brand to reach its target segmentation through your app.

As for how much money you can make through partnerships, the sky’s the limit.

Conclusion

These are just a few ways of how apps make money.

Keep in mind that it’s important to sit down and do some analysis when deciding which ones to incorporate and build your product on.

Not only this but generally if one doesn’t rise to your expectations, there is always the possibility to mix them up and see which combination works best.